Mutual Respect and Support

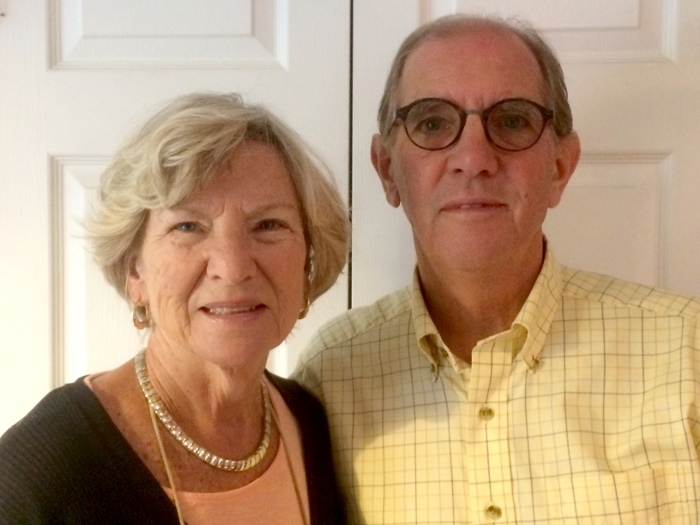

Presented by the Rev. Ann Stevenson and the Rev. Dr. Tad Meyer, husband and wife priests of the

Episcopal Church

In this series of Forums, we are exploring the fascinating realm of intimacy through a spiritual perspective. This morning’s topic concerns mutual respect and support, a subject which on the surface may seem obvious and self-evident, the stuff of wedding vows. In fact, our service of The Celebration and Blessing of a Marriage includes any number of references which hold up the necessity of mutual respect and support. In the opening address of the service, the minister affirms the Divine inspiration for marriage, the second being for the help and comfort given one another in prosperity and adversity. Later in the prayers for the couple, God is asked to give them wisdom and devotion in the ordering of their common life, that each may be to the other a strength in need, a counselor in perplexity, a comfort in sorrow, and a companion in joy which sounds to me like the language of mutual respect and support. And finally, in the blessing of the marriage the priest prays that God will send God’s blessing upon the couple so that they may so love, honor, and cherish each other in faithfulness and patience, in wisdom and true godliness that their home may be a haven of blessing and peace. Once again, it certainly seems to echo a desire for mutual respect and support.

As can be seen from these references, mutual respect and support is, of course, the bedrock of any intimate relationship, the very foundation of intimacy. Without it, we will never be able to bear the daunting, challenging and joy-filled task of exposing our minds and hearts to another human being and daring to look deeply into their selves and souls. We need to trust in their respect and support if we are to take the risk of vulnerability, placing our fragile hearts in their hands and we also need to exercise such respect and support as we receive into our own hands their deepest joys and fears. And yet, as seemingly essential as such respect and support is to the creation and maintenance of healthy intimacy, it is a very difficult thing to exercise constantly and consistently for a variety of reasons. On one hand, who among us would dare to admit that they do not respect their intimate partner or friend? Respect, however, involves a number of different dimensions. If you look up the word in the dictionary, you will find a dizzying variety of definitions which revolve about words such as “esteem” or “deference” or “honor.” Heady qualities to be sure, but is that what we mean when we talk about “respecting” our partners in intimacy? Personally, I would certainly like to think that I esteem and honor my wife and my intimate friends and there are certainly times when I defer to their judgments but I am not sure that such notions really capture the richness and demands of the quality when placed in the context of intimacy. Perhaps by revisiting once again our tripartite model of the human personality, we can begin to explore some of the more subtle demands of the concept.

As we all know, the realm of the “I”, the subject, the personality, is largely involved with what we “do”: what we accomplish and how we accomplish it. In this realm, respect does seem to involve a certain amount of esteem and deference. You may not respect or esteem your partner’s job or occupation but you had better respect and esteem their attempts to engage and exercise it and you need to support them in that endeavor. On a somewhat deeper level, one of the ongoing challenges of long-term intimacy is to maintain respect and esteem for certain personality traits or interests. In the initial throes of intimacy certain personal characteristics and interests may seem impressive and alluring because they are new and so different from the patterns of your own personality. Over time, however, as familiarity breeds a certain contempt, those same qualities may become irritating and seemingly pretentious. At times we may have to actively remind ourselves of how attracted we once were to those personality traits so that we can refrain from losing our respect and appreciation for them. We need to rediscover and reclaim a sense of that original attraction. That is certainly a challenge but it is not impossible and it is a sure and certain sign of respect and support.

Familiarity does indeed breed contempt because it allows us to create projections about our partners that suggest that we actually know and understand them. As I mentioned in an earlier discussion, in my first marriage, after 23 years of life together, I was incredibly good at predicting my wife’s behavior. When we ate at a restaurant, I could predict with 95% accuracy what she would order and when we walked into a store, I could accurately guess where she was going to go and what she was going to look at. I had heard many of her stories as she had heard mine and so when she began telling one, I would check out and occasionally nod to feign attention. After all, I knew the plot, the characters and the outcome so why should I pay attention. I thought that I knew her because I could predict her behavior and was familiar with her stories and in a deep sense that meant that I had lost true respect and esteem for her unique and changing personality. When she stood in our living room and told me that she could no longer live in our marriage, I was confronted with a woman I did not know and whose fault was that? Respecting and esteeming your partner’s personality means engaging it with interest and attention and combating our natural propensity to equate familiarity and predictability with real knowledge and understanding. To support our partners and friends in intimacy involves dismantling our projections and seeking actively to engage our loved ones’ unique personalities, interests and needs. For men this can be extremely difficult.

When Ann and I first were married we discovered a book written by a Christian marriage counselor, Gary Chapman, which has since gone “viral” as they say, appearing in numerous editions and various modes of presentation. The book was called The Five Languages of Love and in it the author presented an interesting model for love that was rooted in his therapeutic experience over the years. His basic premise was that we all want to love and be loved but we have different ways or “languages” of expressing and experiencing love. Chapman goes on to write about five common languages that we use to express love. Gift giving: we tend to give gifts to those that we love. Certainly one of the most common languages that drives our economy, especially during the next couple of days, but on the whole I think it is one of the least effective expressions of love occasionally inspiring guilt instead of gratitude. Physical Touch: we touch the one’s we love, using our bodies, our physicality to express and experience our emotion. We hug our friends and hold our lover’s hand. Words of affirmation: we say nice, affirming things to those we love – even about those personality traits that might have become a bit irritating. Quality time: We pay attention when we are with someone we love. We put down the paper, turn off the TV or computer and listen intently to their stories even if we have heard them before. In truth, the story often changes and then there is always the question of the context of the story: what emotional situation causes them to remember that particular story at this particular moment? And finally there are Deeds of service: we do things for those that we love, helping and assisting them in any way that we can. I am sure that we all have had experience with all five of these languages but Chapman suggests that one of them is your primary language, the way you most profoundly experience and express love. Now what often happens is that two people love each other but they have different primary languages, divergent ways of expressing and experiencing their love. For example a couple comes to Chapman’s office both feeling unloved and unappreciated. After some conversation, he discovers that the husband’s language is deeds of service and the wife’s is physical touch, so she is crying her eyes out in the bedroom because he is not up there making love to her and he is down in the driveway washing her car.

Now Chapman suggests that women tend to gravitate toward the languages of physical touch and quality time while men tend to embrace deeds of service. I certainly fall into that camp and in my experience of talking about this with numerous couples, the vast majority of men I spoke with fell into the category. There is something about our familial, political and social culture (as well as - I am sure - our genetic or biological disposition) that breeds in men this understanding that the way to show someone you love them is to do something for them, in other words, fix their problems. Soooo – the woman comes home after a real annoying or troubling experience – professional or personal – and in the bonds of intimacy she wishes to share her frustration and concerns with her partner. The man listens intently to the situation, even asking sensitive questions for clarification. When she is finished, he decides that it is time to express his love by analyzing the problem and presenting the best solution – a wonderful, caring deed of service. He is shocked, of course, when he does not receive loving appreciation and gratitude but instead is given an angry, icy response as she walks out to go take a shower and he suddenly realizes that he is not going to be lucky tonight despite his heartfelt deed of service.

I know this is a paradigm and exchange that you have probably encountered in other settings or venues but I am sure you see why it is so important in the context of this topic. Driven by his own need to solve the problem through a deed of service, the man unintentionally disrespected the woman and in doing so failed to give her the loving support she craved and needed. She did not want a solution but a respectful, sympathetic ear and an affirming heart. She needed quality time followed by some physical touch and he gave her deeds of service which totally put her off any touching at all. As a representative of my gender, I would love to be able at this point to tell you that I have also seen numerous women do the same thing, but in truth, I haven’t. In fact, although I have certainly benefited from women’s problem solving in various professional settings and have joyfully benefited from my wife’s numerous deeds of service in our marriage, I don’t think I have ever seen or experienced a woman who does not know how to respond with quiet empathic support in an intimate setting. Furthermore, I will confess that it takes an act of conscious will for me not to “problem solve” in responding to those situations and I reckon that I accomplish that perhaps half the time.

In talking about these things, we have drifted a bit from the realm of the “I” to the “me” – the seat of the character, the receptacle of our values, beliefs and emotional needs. When an intimate pairing – partners or friends – share common values and beliefs, it can obviously enrich and energize their ability to share effortlessly some deeply personal information: ideas, thoughts and feelings. Such sharing may even lead them to a better understanding of their emotional fabric and needs. Often, however, intimacy occurs within a relationship where some basic and heartfelt values and beliefs are not shared. How many couples, for example, do you know who don’t share the same political ideals or allegiances or even more poignantly given our context, don’t share the same religious values or beliefs. Couples may have differing theological views on the atonement or the breadth of salvation. They may have been raised in different Christian communities and now belong to different denominations. They may even have different faiths traditions or one may have no faith at all. Such differences in spiritual values and beliefs present a real challenge to intimacy. They can become an ideological mine field where every discussion of religious values breeds suspicion, defensiveness and distrust, not exactly the emotional context for healthy intimacy. With time, they can create emotional and intellectual distance where certain topics or discussions are simply avoided to ensure peace and quiet. Such distance and avoidance, however, is erosive to any healthy sense of intimacy.

In his first letter to the Church at Corinth, Paul talks about differences of faith in married couples and he believes that it should not be grounds for separation or divorce: For the unbelieving husband is made holy through his wife and the unbelieving wife is made holy through her husband. In truth, I am not a great fan of the Apostle Paul when it comes to his understanding of marital dynamics and intimacy. The sub-text of his advice here seems to be that a spouse’s lack of faith should be tolerated so that they might be saved through the worthiness of the faith of their partner. My problem with that notion is that it is devoid of a real sense of respect and support for the others’ beliefs. If we are to live intimately with those who do not share some or all of our core values, we must find ways to respect and support them in their beliefs without sacrificing our own integrity. First and foremost, we must explore with them why they believe the way that they do – not argumentatively or contentiously, but respectfully and sensitively. As we talked about two weeks ago, we must take our personal space into shared space and by doing so invite them to do the same. The only way that that can happen is when they know it is a supportive space that is free of judgment. I have often mentioned the Zen saying that I used to keep over my desk which read Do not seek the truth – only cease to cherish opinions. If we are to create such intimate spaces where self can emerge we need to leave our cherished opinions at the door and extend our hearts in respect and support to the one we love. Mutual respect and support allows close relationships to create shared spaces where they feel safe enough to bring their deepest joys, concerns, beliefs and fears and to place them in the hearts and hands of another. As I mentioned before, it is through such space and the exchanges they inspire that self emerges and we enter into the creative realm of intimacy. Mutual respect and support creates spaces where we can be ourselves without fear of judgment or rejection. As John writes Perfect love casts out fear and so it does even amongst us poor mortals.

What we deeply fear is that when we open our mind and heart to another, when through the vulnerability of intimacy we expose to their gaze our deepest selves, that that person will balk at the sight and shudder with disgust and contempt. We fear rejection and judgment and often that fear prevents people from engaging intimate relationships. It is love expressed through mutual respect and support that allays that fear and allows for a dynamic of trust and acceptance that inspires deeper intimacy.

Wendel W. Meyer

3901 Davis Blvd., Naples, Florida 34104 239-643-0197 Office hours 9 a.m. to 1 p.m. Monday-Friday