Forgiveness

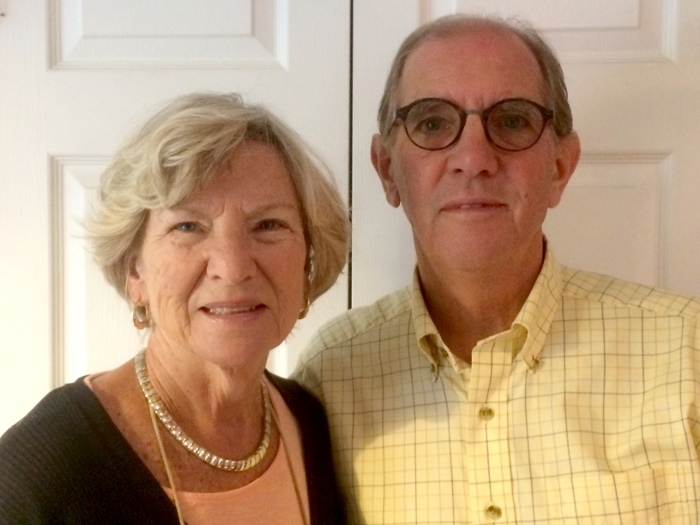

Presented by the Rev. Ann Stevenson and the Rev. Dr. Tad Meyer, husband and wife priests of the

Episcopal Church

In this series of Forums, we are exploring the fascinating realm of intimacy through a spiritual perspective. This morning we will talk about a spiritual dynamic that is absolutely essential to the creation and maintenance of a healthy intimate relationship: forgiveness. The dynamic of forgiveness, however, is one that is woefully misunderstood and because of that it frequently leads to confusion, frustration and exasperation.

One of the most prevalent misunderstandings about forgiveness arises from the fact that it is so often seen in legal or judicial terms, in terms of pardon or amnesty. A wrong is committed, a wrong which clearly deserves some sort of punishment, yet when the accused is brought before the tribunal of justice, that wrong is graciously pardoned by a magnanimous judge. The problem with this concept is that it is devoid of any sense of real relationship, of any understanding of intimacy. What holds the judge and the criminal together are the limits of the law, a frame of reference defined by a mutual understanding of right and wrong and the legal parameters of crime and punishment. Yet, in reality the demand for forgiveness rarely occurs within such an orderly setting. Far more often, the need for forgiveness arises within the muddled waters of human relationships, between spouses, siblings, parents and children, between partners, lovers and just good friends where clearly defined parameters of right and wrong are often non-existent. Within the tangled web of these intimate relationships, the demands of forgiveness become far more convoluted and confusing. More often than not, within such relationships, there is no consensus on a framework of justice, on legal limits of crime and punishment or even the existence of the offense. How many times are we more than willing to forgive if only the offending party will acknowledge that they have done something wrong? How often have you been eager to forgive your friend or spouse if only they will admit that they have violated the “rules” and actually hurt your feelings? So often, in the bonds of intimacy, when we sit behind the bar of justice, we discover that we are quite willing to be magnanimously merciful if only the accused would acknowledge their need for mercy. When the matter of forgiveness is placed within the complexities of personal relationships it becomes a highly ambiguous affair which clearly does not fit the judicial model or mold and yet, as we all know too well, it is within just such relationships that the most ardent and incessant demands are made on our ability to forgive.

In truth, within human relationships, forgiveness is not a legal transaction which takes place between a victim and an offender, but is instead a desperate struggle within the confines of the human heart and soul. The Greek verb "to forgive" is aphieme which can be translated to release from one's grasp, to let go, to free. Through an act of forgiveness, we are asked to let go of something, to release it from the grasp of our minds and hearts. Within the fragile chambers of the human heart, where lines of culpability and responsibility are so often hopelessly blurred, what we must let go of is our anger, our sense of self-righteousness and our resentment. We must let them go because what we are so desperately seeking to free is none other than our own minds and hearts. It is so important to realize that we forgive – not to change others, not to make them alter their ways out of feelings of guilt – but to change ourselves, the way that we feel and think. Forgiveness is not about pardoning the offense of another but is about freeing ourselves from feelings and emotions that will become toxic and destructive if they are not expelled. To perceive that truth is to begin to understand why Jesus commanded his disciples to practice unlimited forgiveness, to forgive not seven times but seventy times seven. Jesus was not talking about forgiveness in terms of a legal ledger, a score card upon which we mark down the number of times we forgive those who offend us. No, he was talking about forgiveness as an attitude, a way in which we relate more to ourselves than to other people. He was holding before us a way to cleanse ourselves of toxic thoughts and emotions which can cripple and even destroy our capacity for joy and intimacy.

Forgiveness within the framework of intimacy, however, is a very complicated and difficult affair, which we can clearly see if we return for a moment to our tripartite model of the human personality. At times, the demand for forgiveness comes within the “I” mode, the subject of a person, the doer or as we discussed last week, the vessel and vehicle of the personality. Here forgiveness is not terribly demanding given the rather superficial nature of what we have to let go. Let’s say, for example, that Ann and I are driving to a particular shop that we have only been to once before. I think that it is down the next street but as I put on the blinker, Ann protests and insists that it is two streets down. I click off the blinker, go two streets down and turn but we discover that I was actually right and we have to turn around and head back two blocks. Ann questioned my judgment and there was a prick of irritation at having it questioned and, of course, there was a feeling of vindication when I was proved right. My irritation – especially in light of vindication – is a relatively easy thing to let go of and by the time we enter the shop – all is forgiven. Assaults on our personalities are relatively easy to either dismiss as unsubstantial or to forgive, to let go of the anger and resentment, because in truth, more often than not, there is really not that much at stake.

Attacks on the mode of the “me”, the realm of the character, are far more threatening and much more difficult to deal with. You’ll remember that the character is the seat of our values and beliefs, the building blocks of our self-perception. Let’s say in this instance, I am with a good friend that I have come to like and trust. We have not, however, talked about our religious beliefs and one day as we are walking along, I make mention of my faith in God. He looks shocked and horrified and then ridicules me by saying that he can’t believe that an intelligent person would still cling to faith, obviously a comforting delusion but a delusion none the less. Here we see that much more is at stake and hence letting go of the feelings of hurt and resentment is very difficult if not impossible. We may be able to let go of our anger and resentment but if the integrity of our beliefs and values is truly threatened we may have to end the relationship. I once had a friend who was dead set against the ordination of women: theologically, spiritually and politically. Even though we stopped discussing it, I found I could no longer be his friend because the ordination of women was not a theological theory or a political point of view for me but was a highly personal matter since my life was inextricably and joyfully linked to one of the finest priest I have ever known and I found that I could not befriend someone who questioned the authenticity of her calling and ministry. When someone questions or attacks the tenets of the “me” – the pillars of our character – even if we can let go of our anger and resentment, we may find that we cannot maintain the relationship and still preserve our integrity.

There is, however, the final component of the personality, the illusive but essential sense of “self” which is, as we have seen, the arena for intimacy, for the sharing and experiencing of our deepest fears and most profound joys. Here the act of forgiving is profoundly difficult and challenging. As I mentioned last week, such intimacy requires vulnerability as we literally place our hearts in the hands of another revealing to them the tattered but vital layers of our souls. Within such intimate relationships, severe damage is often done, sometimes intentionally – sometimes unintentionally. These wounds go even deeper than our cherished values and beliefs, striking at the very heart of our self-perception. Once wounded, it is so hard – so very hard – to open our hearts in trust again, to once again place those hearts in the hands of the one who hurt us. And yet, inevitably it is what is demanded, time and time again in every intimate relationship, if it is to survive and flourish. In my first marriage, such deep and penetrating wounds were inflicted early on and there was no real forgiveness and so for years, we lived a life of close proximity, of shared space, with no real intimacy. We were wounded and grew wary of each other and our sense of intimacy withered and died. We edited our thoughts and feelings, sharing only what we thought was safe and what was necessary to maintain our shared space and life. We did not forgive one another at the deep level of “self” and so we did not trust each other and were not free to be our true selves in the context of our relationship. For the last fifteen years of our marriage we lived in the spatial confines of the institution of marriage with no real sense of life-giving intimacy. Intimacy demands forgiveness and to let go of our sense of hurt and betrayal, to release our feelings of wariness and defensiveness, requires a reckless love rooted in a deep and graceful desire for redemption and healing.

For Christians, the paradigm of all forgiveness was revealed on a wooden beam on a hill called the skull. At that supreme moment of human history, we are told that Jesus forgave those who put him to death, those who tortured him, betrayed him, scorned him and denied his life and ministry. Why did Jesus forgive them? Forgive Pilate, forgive Caiaphas, forgive Peter, forgive the soldier who drove nails into his flesh? Was it because he sought to restore those relationships? Did he expect those people to change, to suddenly repent of their actions and pull him down from those bloodied beams? No, Jesus forgave them because it was his nature, it was who God called him to be. Jesus forgave them in order to complete the work of healing that marked his entire life and ministry. Jesus forgave them because by doing so he healed himself, he made himself free, free to be the person he was called to be. Jesus forgave them and then he prayed with a heart broken by betrayal that his example would inspire others to change as well, to become vessels of incarnate love. And so it has which brings me, my friends, to my final point: if forgiveness does not feel like a cross, than chances are you have grabbed hold of something else.

Wendel W. Meyer

3901 Davis Blvd., Naples, Florida 34104 239-643-0197 Office hours 9 a.m. to 1 p.m. Monday-Friday