Introduction

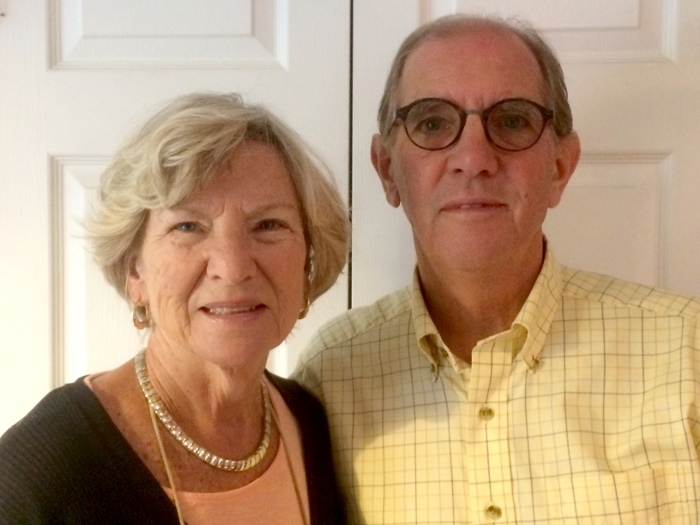

Presented by the Rev. Ann Stevenson and the Rev. Dr. Tad Meyer, husband and wife priests of the

Episcopal Church

In this series of Forums, we are going to be exploring the fascinating realm of intimacy through a spiritual perspective. There is nothing that is more important in our lives than the web of intimate relationships that support, sustain and challenge us. In our marriages, families and friendships we strive to engage and deepen those intimate bonds that are so essential to our happiness, growth and self-awareness. In this series of forums, we will focus our attention on some of the spiritual values that are essential to the formation, maintenance and enrichment of those life-giving, transformative relationships. Each forum will begin with two presentations which I sincerely hope will be followed by lively discussion and animated conversation. This morning, as way of introduction, I am going to talk for a bit about the broad theological context for this series of discussions, exploring briefly the dynamic of intimacy and what it has to do with our faith in and our beliefs about the Christian God.

The Christian faith was rather uniquely designed to be a communal/relational affair. Jesus called his followers to exercise their faith in relationships - communally - and he seemed to do so based on some fundamental theological perceptions and principles. We cannot grow into our full stature of children of God on our own. We cannot claim our identity as bearers of the Imago Dei without each other. We need each other in order to live into God’s calling and to experience God’s redeeming graceful love.

Resting behind these assumptions is, of course, our theological understanding of the essential nature of the Divine. We believe in a Trinitarian God. We worship a God whose very essence is communal, a God whose very nature and being is relational. As Christians we are called upon to abide within the love of a Triune God – that love generated by the intimate relationship of the Creator, Redeemer and Sanctifier - and we are to do so within nurturing communities inspired and infused with that communal love. We need each other to become the people God wills us and calls us to be. We cannot become and be the Body of Christ without each other and we cannot experience God’s redeeming love without experiencing it in a relational context, but how? How can we understand the relational dynamic of this communal experience and its relationship to our salvation in a way that enables us to grasp and embrace it?

The fulcrum of this relational dynamic is intimacy and before we delve into those deep waters, we should spend a moment considering what we mean by that term. I discovered one the best models for understanding intimacy in the pages of a book entitled the Art of Intimacy written by two psychiatrists, a father and son named Thomas and Patrick Malone. In that book, they spoke of a triune model of the human personality based on the old childhood retort of “me, myself and I”. The “I” is the subject of the personality, that part of our personalities that is defined by what we have done, what we have planned, implemented and acted upon, equivalent in some ways to Freud’s superego. Here we see and present ourselves through the lens of what we have accomplished: our educational and professional accomplishments, our familial and material achievements, our personal or ethical triumphs. In the “I” mode, the narrative of our lives is written in terms of all that we have managed to accomplish and acquire and it is that part of our personality that we generally present to others since it is by far the safest and the easiest to share. The “me” on the other hand is that part of our personality that is the object rather than the subject; that part that was formed and shaped not by what we have accomplished but by what has happened to us over the course of our lives, those things that we did not instigate but experienced. It is not the story of what we have done but rather the tale of when we have been done to. It is not a part of our personality that we readily share until there is some level of trust and familiarity. When I first meet you, I will happily talk about my “I” material, my personal, professional and educational successes, my family and my hobbies but it is only after I know you and have come to trust you that I will share with you the story of my divorce, or my bout with polio or the failures and challenges that have punctuated my life. Finally there is the third realm of “self”, the reflective part of the personality buried beneath the subject and object. Here is a dark and opaque realm where our deepest fears and greatest desires reside. Here is the font of joy, not happiness; despair, not disappointment. Here is the source of our most profound and most complex motivations, our darkest secrets and our most treasured hopes.

The word intimacy is derived from the Latin intima which means “inner” or “innermost”. It is within the self that our intima resides, as the Malones’ suggest: Inside each of us lies our intima, the deepest core of our person. It is the innermost part of ourselves, our most profound feelings, our enduring motivations, our sense of right and wrong, and our most embedded convictions about truth and beauty. (page 17) Hidden within the intima of self are the true reasons we act, feel and think the way that we do, impulses that often get very distorted and altered when they are filtered through the “I” and the “me”. The realm of the self is not necessarily one that we are conscious or aware of as we make the decisions that chart the course of our daily lives. Often we will think of what we are doing and why in terms of the “I” or occasionally the “me.” We will grab hold of the most obvious and superficial explanation of our motivation which explains why we are acting, thinking or feeling a certain way. And yet, it may well be that there are ulterior motives forming and shaping our action, motivations that are rooted in our deep fears or our most ardent desires, motivations that were forged in the distant past through trauma or joy. It often takes deep reflection and analysis to uncover these layers of the “self” and often what we discover there challenges our perceptions of who we think we are, the identity safely cradled in the “I” and the “me.” As the Malones argue: Your inside being is the real you, the you that only you can know. The problem is that you can know it only when you are being intimate with something or someone outside of yourself. (page 19)

Many of our professional and social relationships operate effectively and enjoyably on the plane of the “I” and “me” but deep within the chambers of the human heart rests the fearful desire to be known fully and to know fully. As Paul so eloquently suggests in the hymn to love in the 13th chapter of 1st Corinthians: For now we see in a mirror, dimly, but then we will see face to face. Now I know only in part; then I will know fully, even as I have been fully known. Paul, of course, is speaking of a theophany but I think that the dynamic he is describing is deeply embedded in our desire for intimacy, for relationships that probe the deepest layers of our self, to be both fully known and fully knowing. We desire it but we also fear it. For many, it is far easier and more comfortable to be left safely within our pretensions, within all those achievements, characteristics and self-definitions that we have carefully crafted to give our lives a sense of meaning and purpose. But others crave a more profound experience and so they enter into intimate relationships where the self, the intima, will be revealed and shared, a terrifying but deeply rewarding experience. Fully knowing and being fully known, being wholly revealed to the gaze of another human being and to look into the patterns of their soul as well – sharing and touching the innermost cores of our beings – this is the essence of intimacy. What we find there is often not pretty and is often challenging but it is the way in which we become fully human, exposed and exposing the full extent of the glorious and terrifying complexities of our human nature.

It is through engaging intimate relationships that we enter into the realm of “self” and take the risk of knowing fully and being fully known. Such intimate relationships, often unwillingly and unwittingly, force us to expose those deep fears and desires to the gaze of another and they also invite us to see within another person similar patterns of apprehension and longing. To engage such intimacy is to be changed, changed in ways that are often out of our control. I am sure that many of you watched that wonderful BBC series Downton Abbey. In the 4th season. Lady Mary, continues to struggle with the sudden and tragic death of her beloved husband Matthew, trying desperately to sort through the complex and confusing legacy of intimacy that marked their relationship and marriage. In one episode, her grief seems to be receding a bit and she hesitantly begins to engage her life, going for a ride with the dashing, sensitive house guest, Lord Gillingham. Riding along, Gillingham tells her that she must feel fortunate to have experienced true love. She hesitates and then says rather surprisingly – “Maybe, but it has changed me – he changed me.” It is both an expression of gratitude and a lament – an expression of dramatic emotional ambivalence. We all say that we want to change but rarely do we truly desire to embrace it. More often than not we simply want things and circumstances to change so that we can be more comfortable being who we think that we are. Intimacy forces us to change on a very deep and profound level and that change may confuse, confound and startle us. It is change that is not engaged at our behest nor is it a process which we control or direct. It is a current of emotion and insight that will carry us where it flows not where we will it to be channeled.

We are creatures of enormous pretension and left on our own we would do anything to avoid being simply human. We are constantly judging and competing with those around us, even those we claim to love. Put your finger on your pulse and see how you feel when you hear these words: common, average, ordinary. If you're anything like me, those words ring with a disparaging tone. They are not adjectives with which I like to identify. After all, do you like to see yourself as common? Do you like to think of your children as average? Even in rustic Lake Wobegon, Garrison Keller tells us, all the children are above average. And do you really want to envision your life as ordinary? We have been raised, or perhaps more accurately, we have been inculcated, with the belief that we are special, and that our "specialness" protects us from suffering the unbearable curse of being ordinary, average or, heaven forbid, common. Do you really aspire to be an ordinary human being?

In the Prologue to The Art of Intimacy, Thomas and Pat talk about the grand discoveries of Archimedes, Galileo, Shakespeare and Madame Curie speculating about the wondrous sense of connection they must have felt as their skill and talent led them to an aspect of “the integral truth that is the universe.” They go on to note:

We can say that these were special people who had special experiences. But if we do, we make the mistake of “civilized man”: the mistake of believing that being connected to the universe and to the universality of truth is “special”; that only the few who are talented or powerful, beautiful or rich, socially titled or spiritually saved – or whatever the hierarchies of the times valued most – only those few can feel themselves at the center.

As the authors suggest, we are all capable of being deeply and profoundly connected to the “integral truth of the universe” and to live lives of faithful integrity. To do so does not require that we exercise special gifts or associate with special people. Rather it requires that we embrace the common humanity that rests at the very heart of what it means to be a human being. Through the glory of the Incarnation, God has made that common, average, ordinary humanity the vehicle of our salvation and it is through our intimate relationships that we are invited, challenged and sometimes forced to embrace our common, average and ordinary selves. In the great irony of intimacy, it is only when we become completely human, no better or worse than any other human being, everyman or everywoman, that we truly and gloriously become our unique individual selves, joyfully reflecting the image of the Triune God.

As you can see from this brief reflection, the dynamic of intimacy is one that I feel has enormous importance and significance. In fact, I would argue that such intimate relationships are the raison d’etre of human existence, the very reason that we were created in the image of God. It is through our intimate relationships that we become fully human and it is that humanity which is the pathway to the Divine – Creator, Redeemer, Sanctifier. Paraphrasing Athanasius in his treatise on the Incarnation: God became human so that humans could become Divine. It is, I believe, through the marvelous dynamic of intimacy that this continuing work of Incarnation is carried forward. Over the course of the next few weeks, we will explore various spiritual characteristics and disciplines that enable us to engage the dynamic of intimacy. Next Sunday we will begin by focusing on self-awareness and understanding.

Wendel W. Meyer

3901 Davis Blvd., Naples, Florida 34104 239-643-0197 Office hours 9 a.m. to 1 p.m. Monday-Friday